The Marlon James Article Dissecting Kendrick Lamar’s Lyrics

in “The Blacker The Berry”

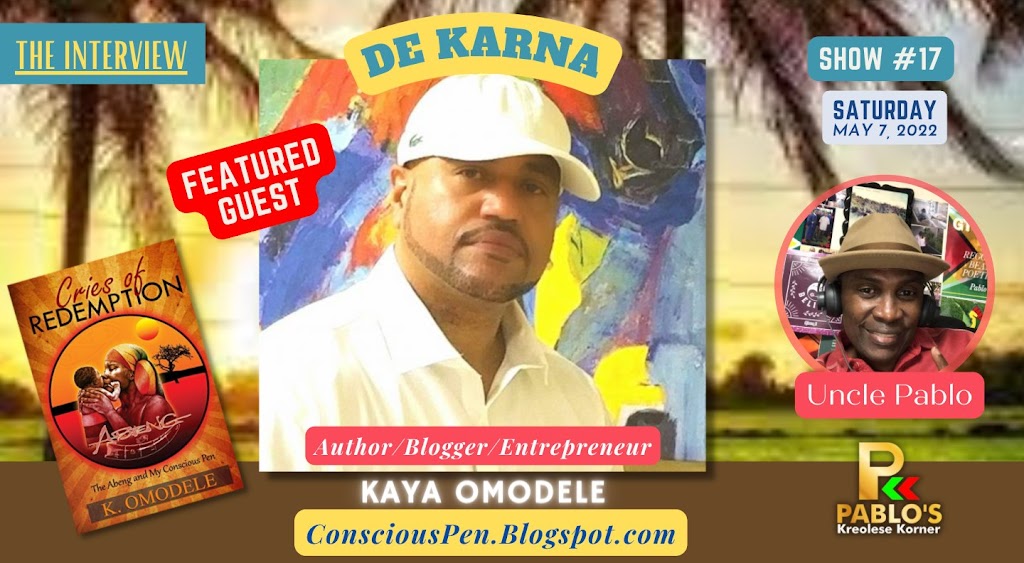

by Kaya Omodele @TheAbeng

At first glance, Marlon James’ article “The Blacker The Berry” in The New York Times Magazine had me squinting my eyes, wondering how he could be so out of tune. In this issue, 25 Songs That Tell Us Where Music Is Going, Marlon was reviewing hip-hop artist Kendrick Lamar’s The Blacker The Berry (from the album To Pimp A Butterfly); but in my opinion, the writer wasn’t getting the fullness of the lyrics. Not that I didn’t understand Marlon’s views and conclusions, I just couldn’t believe how off-key he was in interpreting Kendrick’s art.

Take for instance Kendrick’s lyrics in the third verse:

“It’s funny how Zulu and Xhosa might go to war…/ Remind me of these Compton Crip gangs that live next door.”

Marlon James response was that “…those are two nations going to war. And, fine war is hell, but if Britain and France aren’t called thugs for Waterloo, if Lancaster and York aren’t called bangers despite literally being family killing family, then why do Zulu vs. Xhosa get compared to warfare?”

But wait, Marlon, firing logic based on presumptions implying that Kendrick doesn’t or wouldn’t label those European combatants as thugs or bangers, indicates you have missed the whole target in the comparison. He’s not reducing Zulu and Xhosa nations’ war and comparing it to gang warfare; he’s implying that it’s black-on-black violence either way. Whether it be gangbanging, PNP vs. Laborite*, Hutus vs. Tutsis, despite the different ideological causes of these conflicts, they’re all the same kind of tribalism/tribal war. It’s black people killing black people, that’s the point. You’re making it about something else, even though your point is generally valid.

Then, Kendrick spits:

“So don’t matter how much I say I like to preach like Panthers/ or tell Georgia State ‘Marcus Garvey got all the answers’/…So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street/ When gangbanging make me kill a nigga blacker than me? Hypocrite!”

Marlon’s take on these lyrics amazed me.

“…a black man invoking the detestable slogan of black-on-black crime to prevent himself from mourning the unjustifiable homicide of a black boy.”

What!? the author was off base, again. Marlon’s disconnect to Kendrick’s lyrics had me shaking my head. (…to prevent himself from mourning…?!!)

But finally, near the end of the review, Marlon had one of them ah-ha moments and gained clarity that Kendrick’s narrative is a work of fiction that reveals truth; that Kendrick isn’t speaking to or for the community, that Kendrick is speaking AS the community- those of us who may have cried over Trayvon and yet been contributors to black-on-black crime.

Still, I questioned if Marlon REALLY gets it when he further states that Kendrick’s point of view “was just a man wondering how someone gets to be part of the Black Lives Matter conversation when black lives don’t matter to him.”

That’s not what I get from Kendrick’s words. For me, the lyrics highlight the duality in humanity- the good and bad in us all. How we can cry for injustices whipped across our backs, yet crack the same whip against others, just the same. Who feels it, knows it!

A man’s perspective is based on his own experiences.

*political party conflicts in Jamaica